The

Children's Opera "Brundibar" Belongs in a Museum, Not a Theater

The time is January, 2002; the setting, the interior of

the largest, most respected church of a German city: Accompanied by music

conservatory students, a class of local school children is about to perform

"Brundibár", a famous children's opera from the Theresienstadt

Ghetto. An ambitious program of related events is on offer, and, under

the auspices of the state bishop and governor, impressive speeches serving

to remind and warn have been given. The seats are filled with people of

all ages, and the places of honor, in sight of all, are filled by older

women who as girls had been among the performers of the opera in Theresienstadt,

a transit camp to Auschwitz. These women will be available for questions

and comments after the performance, indeed after all six performances.

The house lights are turneed off, and in the remaining auroral glow roughly

30 children parade oppressively onto the platform-cum-stage, all in dirty-gray

cloaks onto which are pinned screaming-yellow Stars of David. The children

throw the cloaks off, form a semi-circle, spotlights bathe them in glimmering

morning light, the music begins, and they start to sing: radiant children

in adroitly fashioned clothes such as could still have been worn in Germany

in the 50s, These are normal children, happy at the chance to sing, act

out and present something. Just ordinary, every-day children.

A scene can hardly be more moving.

And then a plot unfolds that plummets this audience member -- who sees

seventy years worth of German-Jewish history in a practically unbearable,

condensed version before him -- into a swarm of emotions. Played out in

front of him is not the advertised tale of cunning resistance that ends

in a peaceful singing competition. The children gang up against someone

weaker who happens to belong to an itinerant community; the children are

violent with him, degrade him and finally drive him away. Intentional

or not, the hunted-down figure in many ways cannot help but bring to mind

the quintessential Jew. The very German-looking girl who plays the figure

is outfitted in a black smock and black pants. She wears a black top hat,

and a thick black beard and eyebrows have been painted onto her face.

Beside himself, the audience member begins to study the text of the opera

as well as its historical background. All this leaves him no peace.

The time and place of the opera's origin are key. "Brundibár"

was written in Prague already in 1938, too early to have any associations

with concentration-camp culture and resistance. The opera's librettist

would later go into exile; its composer was later murdered at Auschwitz.

1938: it would be another year before the Nazis would march in and officially

brand the composer and the librettist "Jews" because of their

ancestry. 1938: It was a time when the composer and librettist belonged

to a minority of Germans living in Prague. Both were baptized with German

names (Adolf Hoffmeister, Hans Karl Krása); German was the mother-tongue

of both; both studied at German universities; both published in German.

The children's opera was originally composed in Czech only because it

was intended for submission to a State competition. Its first performance

took place in 1942 in Prague's Jewish orphanage, in secret, in front of

a small audience, as Jews were no longer allowed to perform publicly.

From there, the opera made it to Theresienstadt, where it became an out-and-out

success, a legendary pillar of concentration-camp culture. It helped many

of the camp's young inhabitants, who lived in continuous fear of being

shuffled off to Auschwitz, find a happy distraction: A consequence that

was recognized and put to use by the camp's German authorities (see Milan

Kuna's account in "Musik an der Grenze des Lebens" [Frankfurt:

Zweitausendeins, 1998]). The Nazis used an excerpt from the opera's final

chorus in the propaganda film "Der Führer schenkt den Juden

eine Stadt", and had the opera performed for a delegation of the

international Red Cross, which had come to inspect the camp.

The opera's plot is quickly summarized: A brother and sister cannot afford

to buy their sick mother milk for her coffee. The siblings try to earn

money by singing on the streets but are foiled by disinterested passersby

and an organ grinder who makes it clear to them that the streets are his

rightful turf. (The opera is named for this organ grinder.) Eventually

a chorus of three hundred school children bands together, and the strength

of the combined voices makes it impossible for the organ grinder to be

heard. Money for the milk is collected, and Brundibár is humiliated

and driven away forever. The final chorus praises the community spirit

won through this "war" and encourages the children of the audience

to model themselves after the children of the play.

What springs to mind immediately is the imbalance between the root of

the conflict and its resolution: The call-to-arms, all the strong words,

all the drama -- all this for a bit of milk? Indeed, in gruff contrast

to the insignificant cause, an elaborate drama is built on the most basic

of material: the conflict between the cold egotistical, money- and rule-oriented

adult world and the children's world, where kindheartedness, spontaneity

and enthusiasm are what count. When Aninka and Pepicek, at the beginning

of the story, quite rudely demand milk of the milkman instead of asking

him politely for help; when they naively and inconsiderately "move

in" on the organ grinder's business; when they get on the nerves

of the passersby: all this is dramatic "method," as are the

policeman's instructions on the meaning of money and Brundibár's

rebuke of gentility. The children are unrefined and raw, but goodnatured.

The opera is partial to them, while the adult world is ascribed the "unjust"

qualities that make the world a modern one: lawfulness, trade, professionalism,

conventions.

As the opera's acts change over, it becomes clear that indeed everything

essentially revolves around the conflict between the old world of the

adults and the new child-friendly one. It is evening, the children have

experienced set-back after set-back and are at a loss for what to do.

Then, Nature itself, in the form of Sparrow, Cat and Dog, intervenes and

offers advice and assistance, thereby making it clear that Nature is on

the children's side. In order to defeat the powers of evil, it is necessary

to band together with as many children as possible. The start of the new

day is as poignantly underlined by music as was the previous evening,

heralding a new time. Appropriately hopeful and happy, the children and

animals join forces in a "war" in which there is much more to

be won than the small amount of milk money whose absence set everything

in motion.

The children grasp that banded together with others they are strong. Though

their friendship with the animals lacks any real basis, it is powered

by a catalytic agent: namely, Brundibár, who has been decreed the

enemy, and against whom the majority of the school children are prejudiced.

And, because he is an itinerant and outsider, Brundibár is easy

enough to isolate and defeat.

The children also make an important musical discovery. The organ grinder

was able to satisfy the public's musical tastes, something the children

were previously unable to do. Aninka and Pepicek now learn that if they

step in time to a romantically folksy ditty, not only are they able to

muster up both courage and community spirit among all the children, but

are also finally able to reach the adults in a way the organ grinder's

mechanically reproduced music could not: moved, the adults turn away from

the organ grinder towards the children and give them the money Brundibár

was counting on to make his living. The musical marketplace operating

on the calculated basis of supply and demand has been replaced by spontaneous,

from-the-heart folk music capable of uniting the masses.

Thus, a new form of society is born: a children's world in which you do

not have to pay for the absolutely necessary things in life; in which

you do not have to be professional in order to earn money; where discipline,

manners and rights do not really matter. In short, a child-friendly, folk-like

community operating outside the rules of modern society. Though this world

is not truly realized -- the milkman's business would otherwise need to

be expropriated, the policeman driven away, etc. - we nevertheless sense

that this world is on the way to being established via the targeted elimination

of the one figure who least belongs: Brundibár the organ grinder.

His existence is, in the end, the most fragile; he is the one recognized

as both a foreign influence and alienating presence, the one working with

small capital invested in modern technology, the one dependent upon financial

returns (however small), the one dependent upon the preservation of manners,

customs and decency, the one who is professional and market-oriented,

the one who shoos away the annoying kids, the one who stands in the way

of folk culture.

Resistance is not the true "message" of the children's opera

Brundibár (there would otherwise have to be a struggle against

something or someone genuinely strong; against the true powers-that-be),

but rather a rebellion against the symptoms of the modern world. A rebellion,

moreover, that fails to change any actual balance of power and instead

projects its antipathies on a substitute for those symptoms: a scapegoat

who turns out neither to have access to, nor the protection of the powers

at hand, who is suited for isolation and the embodiment of evil.

It should not come as such a great surprise that Brundibár is portrayed

with "Jewish" characteristics. "Strange" and "bad,"

as defined by the opera's world view, are, on the strength of historical/sociological

clichés, all too easily associated with "the Jew", and

it follows that the opera's world view is associated with Fascism. This

Fascism is the direct result of the opera's established patterns of thought

which dictate that contemporary woes be equated with "the Jew"

as modernizing agent and destroyer of folk society. The reality behind

these patterns does not have a thing to do with actual Judaism, but rather

with objective exclusionism and subjective demonization.

Brundibár -- on the borderline of society yet also part of "the

system;" with acapital-based mode of production; with his success

in the market (attributable to his support of technology and advertisement,

his dependence upon even the smallest income, the protection of police

and polite society) -- clearly leads a "Jewish" existence. He

is denounced as worthless, uncreative, greedy and hard-hearted, a surreptitious

criminal and bogeyman as well as the enemy of national characteristics.

His very calling name (Brundibár = Bumblebee) devalues both the

man and his work. He is thus saddled with a great many of the characteristics

that make up an antisemitic cliché.

Worst of all, Brundibár is portrayed from the start as an enemy

of Nature, an enemy the animals of the story are all too ready to hunt

and persecute: The dog, barely awake and only just introduced, hankers

for Brundibár's flesh and blood.

Hidden beneath the fairy-tale trimmings, the opera is about establishing

Brundibár as the object of eliminationist antisemitism.

It follows that Brundibár's fate its also a Jewish one. What he

suffers is a naively played-down, hate-filled Pogrom, replete with pack-of-hounds

and hunt imagery (the Dog: "Spuer' ich einen Hasen auf, / folg' ich

niemals seinem Lauf./ Ich allein krieg' keinen Hasen klein./Hol' ich Freunde

mir dazu, / hat der Hase keine Ruh. / Eine Meute ist des Hasen Pein!"

The official English translation reads: "When a Russian greyhound

mean / stalks a rabbit quick and keen, / watch the clever rabbit outsmart

him./ But, if many Russian hounds / chase the rabbit on their grounds,

/ chances to escape are slim.") . Both the children and the animals

look at the opportunity to "get" Brundibár as something

of a festive hunt they are all too glad to join. This hunt ends in the

degradation of Brundibár, who is both bitten by and thrashed around

by the dog, who has got Brundibár by the pants. ("By the pants":

Something with particularly dangerous and obscene associations for a circumcised

male Jew -- see for instance Louis Begley's Wartime Lies [New York:

Knopf, 1991]: cf. quotation 15 in Brundibár / Essay: click

on the left side).

No one, not even a child, responds to Brundibár's cries for help.

Further, this is the place in the opera calculated to elicit the most

laughter from the children in the audience. Germans can't help but recall

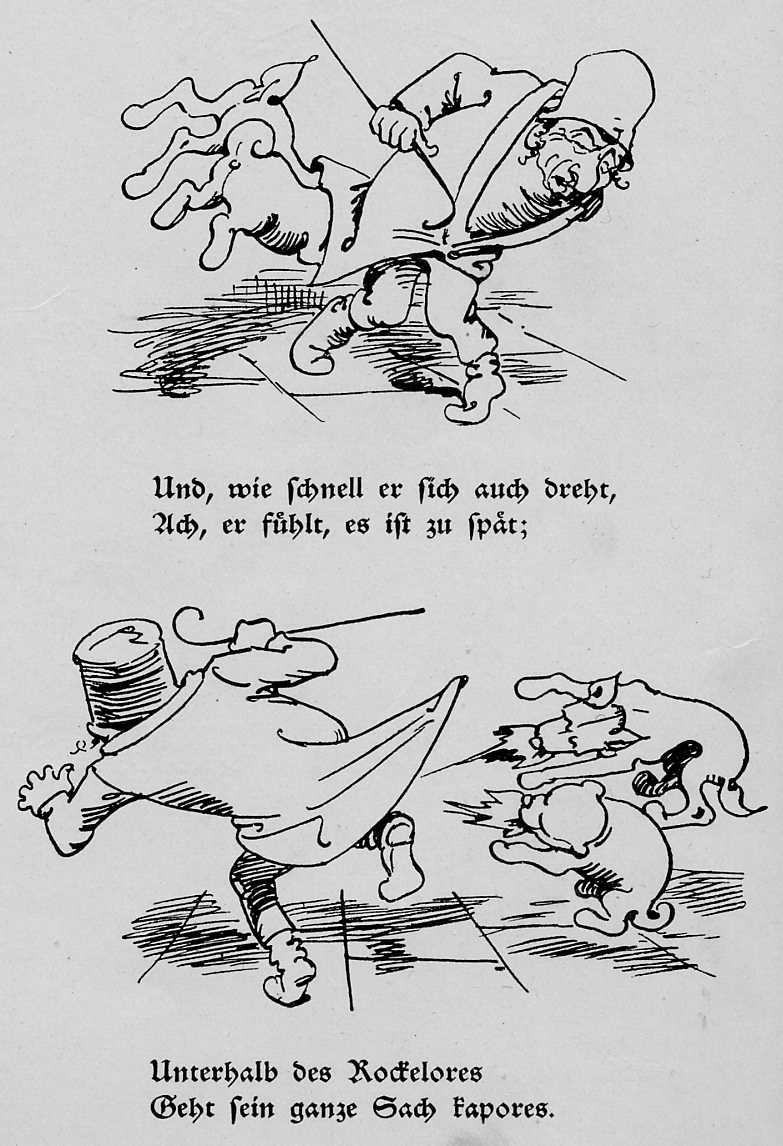

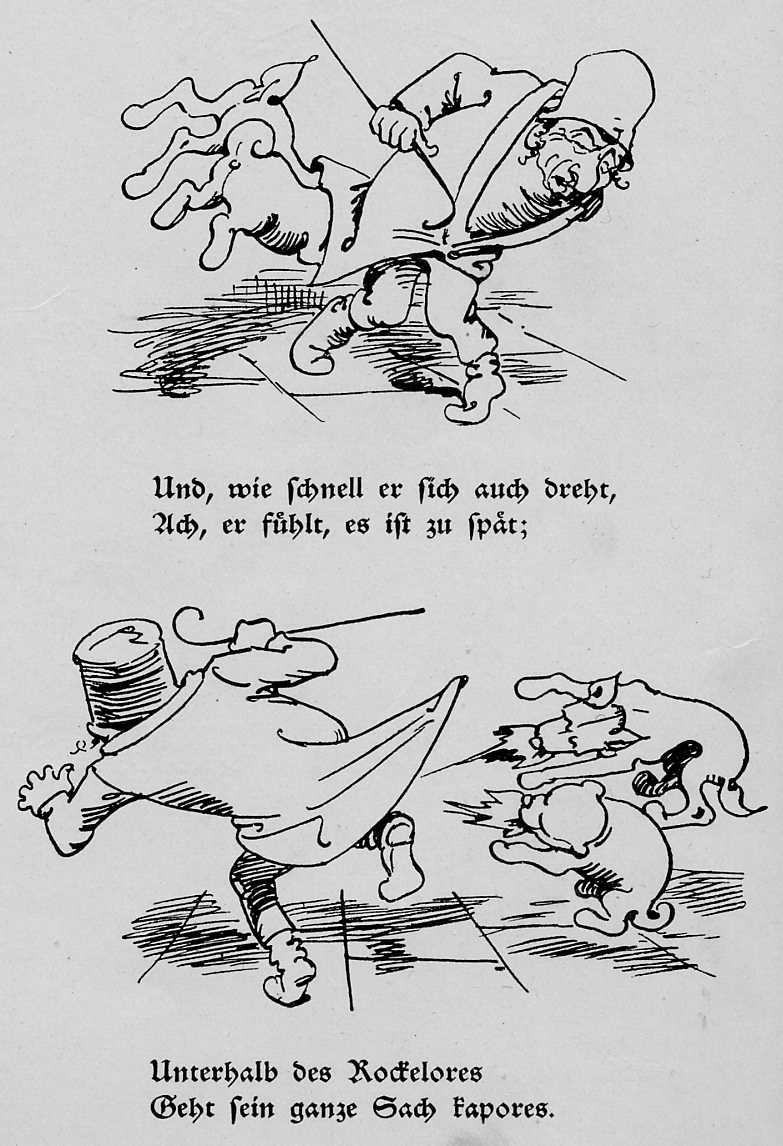

Wilhelm Busch's popular Schmulchen Schievelbeiner (from the end of the

19th century):

(Despite all his squirming effort,

He realizes it's too late for him.

Underneath his cloak

Everything gets spoiled.)

These Busch cartoons are perhaps the most famous to disdainfully

represent the Jew. The dogs ("Plisch and Plum") do not have

any particular reason to be angry: its enough that a Jew should walk by

to set the generations of children who grew up with the cartoons to laughing

at what follows. In the case of Brunfibár, the Dog even takes pleasure

in his intentions to bite the organ grinder, and carries out his deed

of his own accord, backed by Nature's authority.

The inhumanity, fascism and antisemitic tendencies here diagnosed cannot

be misconstrued, despite the story's seemingly harmless surface narrative.

But how can it be that the above tendencies have gone largely unnoticed?

Why is it that even today, despite an internationally-minded audience,

for whom Brundibár has become a hit, no one thinks to raise a protest?

The deciding factor is that the title figure is not identified as a Jew.

He is portrayed as being neither really Jewish nor even comically Jewish

(as is Busch's Schmulchen Schievelbeiner, who speaks pseudo-Yiddish).

Countless eastern European Jews would certainly have had to live at the

very bottom rung of Society's ladder, many may even have eked out a street-musician's

existence; and almost all would certainly have worn a black cloak and

black hat. The quintessential organ grinder was, however, not Jewish,

but Italian, accompanied by a trained monkey. He was also a wanderer,

decried for his thievery. (Brundibár does have to stoop to stealing,

and Aninka and Pepicek at one point play dancing apes to his music; also,

organ grinders were historically often crippled veterans of the first

World War, whom the State supported by lending them street organs with

which they could earn money: this, perhaps, explains the children's mocking

of Brundibár as a "musician without legs" in the original

Czech text.)

Had Hoffmeister and Krása really intended to attack their forefathers

with antisemitism in Prague in 1938 they would have called the object

they wished to denounce by name.

How is it that the opera's dangerous world view, which so easily serves

the antisemtism of the time, has remained latent, and is even today so

easily overseen and obscured? In an informative autobiographical account,

the composer offers a clue:

The biggest problem in planning this children's opera was certainly

the libretto. The usual dramatic conflicts -- erotic, political, and

the like -- were, of course, not usable. Fairy tale lore suited neither

me nor the librettist. Despite this, the writer was able to come up

with a book that is entertaining to children and at the same time an

important comment on real life, in that it plainly shows how important

it is to band together against evil. In this children's opera this is

demonstrated by the singing war between the children and the organ grinder.

(Cited in Kuna, p.2O7)

An artist's intentions could not be more harmless, yet

the account contains all the ingredients of a calamity in the making.

Inspiration for the children's opera was apparently intended to come not

from fairy tales but from "real life." In order to please the

children of the audience, however, a political perspective and any thought

of a serious societal critique had to be abandoned. We have seen just

how the weak dramatic motive (the missing milk money) so easily became

politically charged with the criticism of contemporary conservative culture;

how "reality" (the adult world) was established as decayed and

in need of renewal (by the children). And because this reformation of

reality -- the deliverance from the evils of the modern world -- would

not be able to occur through political means, it fell to a rebellion involving

unfettered Nature (reflected in simplicity and naivety of children and

folk culture) and an all-out "war" against those on the borderline

of society. The idea itself of the decayed modern world; the abandonment

of politics; the "banding together," the collective displacement

of woes on an outsider: these are all symptomatic of the folky, fascistic

and antisemitic patterns of the day.

The opera's latent fascism and antisemtism were not planned. They are

the products of an artistic failure. Krása and Hoffmeister were

apparently the kind of conservative rebels and political romantics who

suffered under the alienating symptoms of modern society without knowing

how quite to counter it other than by running away from it and back towards

the comforts of unrestrained nature, folk society and naive art. The project

of the children's opera unwittingly landed them with a loaded and dangerous

mix: a reality-based impetus with societal critique with regression to

atavistic thought patterns and a ritual casting-out of someone stigmatized.

Fascism and antisemitism out of a test-tube; monsters left free to awaken

as Reason dozed off.

An interesting side-note betrays just how close Krása and Hoffmeister

had come to portraying the dire realities of the time: in Prague, one

year later, Hitler's program of racial cleansing touched the city's organ

grinders. Mussolini had been trying since 1924 to have the organ grinders

recalled to Italy; it was felt that they were giving Italy a bad reputation.

No reproach ought to fall to those who, upon deportation, took the opera

with them to Theresienstadt. The destructive message of the opera, as

outlined above, was perhaps just what made it acceptable for the Germans

and those cooperating with them to have the work performed there (while

attempts to perform other antitotalitarian works in Theresienstadt, such

as Ullmann's "King of Atlantis", were met with death sentences).

It remains decisive that in the end the children of the camp had something

to act out and sing and to give them courage.

These children were themselves uprooted, in a foreign setting, living

in fear of death. In such situations people are apt not to rebel against,

but side along with their tormentors, a phenomenon known to psychologists

as "identification with the aggressor."

In "Masse und Macht", Elias Canetti writes that the people most

susceptible to mob mentality are those living in fear of death (Canetti

uses the word "Meute" when referring to mob mentality; the German

word is used when referring to hunting with a pack of hounds). This would

certainly explain the cathartic effect of Brundibár in Theresienstadt:

In the acting out of something that could only be understood as "good"

by their tormentors they could prove themselves worthy; for once they

could belong to the stronger side, the side which is allowed to hunt down

the weaker side.

It is a very different matter for the German children of today to see

and identify with this opera. With Brundibár today's children are

confronted with something familiar to them as the history of their people;

they are being presented with an example in how to exercise their collective

power on stigmatized outsiders, weaklings and foreigners. What, in the

end, does it matter that today's children are told that the children of

Theresienstadt saw Fascism itself and Hitler in the figure of Brundibár?

This simply makes it all the more difficult, if not impossible, to take

a critical view of the opera's fascistic and antisemtic pack mentality:

if we are up against the most evil villain imaginable, aren't any available

means fair game? And further, isn't the "positive" experience

of attaching oneself to an emotionally strong group valid? The instrument

intended to defeat fascism has taken on the disease's very characteristics.

The famous final chorus of the opera reads:

Freundschaft alle Zeit

Hilft euch in jedem Streit

Und schafft Gerechtigkeit.

(Friendship at all times

Helps in every struggle

And creates justice.)

The unanimity of the mob creates a justice of its own:

vigilantism. What is this but dictated justice and willful force, the

legitimization of violence against an outsider because the violence comes

from children, the legitimization of a "gesundes Volksempfinden"

[healthy folk mentality]?

No less problematical are the historical implications: When the Germans

of today explain the figure of Brundibár as the embodiment of Nazism

to their own children, who copy Aninka and Pepicek yet at the same time

identify with the children of Theresienstadt, they are basically being

told that they are the descendants of victims; that they belong to a people

that once fell prey to someone evil who did not actually belong to their

society and had to be banished. Hitler as Brundibár: The monster

who was not lurking among the natives of our past but was rather the product

of the coldness of modern society, and was, furthermore, of foreign origin

and the outskirts of society. We ourselves are not to blame.

No, this opera, which invites children to mimicry, does not belong on

the stage but in a museum, where it can be considered from a critical

distance and in its historical context.

Performed with great feeling but little critical scrutinization and with

myriad related events, the opera becomes part of the reigning Zeitgeist

which distinguishes itself by coming up with new methods for dealing with

the past on one hand, but debases itself on the other with a neo-liberal

society of a critical, peer-pressured consensus.

On a number of occasions after the performance in the largest and most

respected church of a German city, the audience member, who had been so

troubled by the performance that he was moved to study the opera's text

and historical context, sought to share some of the ideas outlined here.

His ideas were met with frustration and ridicule, and became the impetus

for a hunt that led to public defamation. But this "Brundibár

2002" is another story.

For additional quotations, more informations, bibliography,

links...: visit the homepage and the other "Brundibár"-sites

(click on the left side)!

|

|